| ALL |

|

SARASOTA SCHOOL

| OVERVIEW |

|

| |

The Sarasota School was the name given to a group of architects practicing from 1940 to 1960 in and around Sarasota, Florida, on the Gulf of Mexico. The Sarasota School was one of several regional interpretations of modern architecture in the United States to emerge in the years following the end of World War II, including the Bay Area School in San Francisco and the Case Study Houses group in Los Angeles. By comparison to these other regional movements, the Sarasota School was the least intentional, evolving as it did from Ralph Twitchell’s fortuitous presence during one of Florida’s building booms. From the very start of his Sarasota career in 1936, Twitchell’s work exhibited a respect for the unique landscape and climate of the west coast of Florida, his interest in local vernacular building culture, and his desire to employ newly emerging construction materials and methods to appropriately house the particularly American version of a tropical lifestyle then being defined in Sarasota.

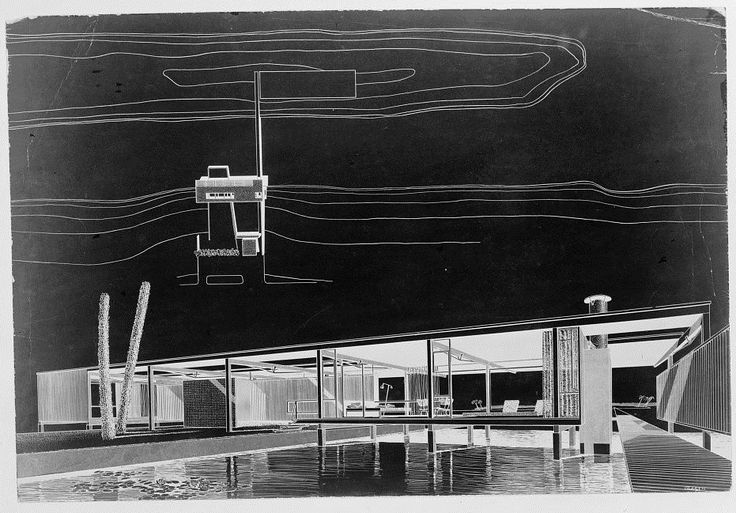

In 1941, Twitchell was joined by Paul Rudolph, who moved to Florida as a result of his interest in Frank Lloyd Wright’s recent works, in particular Florida Southern College. Rudolph was a designer of remarkable ability, and the buildings and projects that resulted from this partnership were astonishing in their consistent high quality. In their designs, Rudolph and Twitchell endeavored to engage the landscape and to develop individual buildings that employed modernist concepts of spatial liberation framed by a complementary urban order. Their project for the Finney residence on Siesta Key (1947), a design that Rudolph had made the previous year while a graduate student at Harvard University, proposed a series of walls, bridges, and dredged inlets that allowed the house to be fully integrated with its site, acting to join remote bodies of land and water while remaining delicately suspended above the landscape. The Rudolph and Twitchell project for six linked residences on the Revere property in Siesta Key (1948) represents a remarkably prescient and constructive critique of postwar American suburban development. These six houses, of which only the Revere residence was built, opposed the typical suburban distribution of houses as freestanding objects, proposing instead a series of plastically interlocked walls and horizontal planes, providing a mix of shade and sun to open-air courts while weaving interior and exterior space to yield both increased privacy and significantly greater density.

The paradise-like settings of the Sarasota School houses, which today appear so lushly “natural,” were in fact the result of a process of ruthless scalping, shaping, and dredging of the original mangrove-covered, water-saturated landscape to produce navigable canals and buildable sites. These newly created and virtually barren lots on the Gulf coast required the architects of the Sarasota School to design not only the houses but also their sites. The result was a series of buildings that subtly wove their sharp-edged geometric forms into the relentless horizontality of the Florida landscape, employing structural and constructional techniques developed for the local climate, economy, and available materials and providing their occupants varied seasonal experiences of sun-drenched interior and exterior spaces. The Healy “Cocoon House” (1950), built on the edge of a canal in Siesta Key, with its suspended rubberized roof secured with cable stays, exemplified the manner in which Twitchell’s interest in engaging new building technologies complemented Rudolph’s capacity to explore their liberative spatial possibilities.

Following the establishment of his individual practice in 1951, Rudolph began to receive significant national and international attention. His Revere model house was visited by more than 16,000 people during 1949. His working relationship with the architectural photographers Ezra Stoller and Joseph Steinmetz (Steinmetz Studio, Sarasota, 1947) was instrumental in Rudolph’s ability to create his own publicity. Skillful photographs highlighted the crisp lines and thin planes of the Leavengood residence built in St. Petersburg (1951), the Sandeling Beach Club built in Siesta Key (1952), the Walker Guest House built on Sanibel Island (1952), and the Hiss “Umbrella House” built on Lido Shores (1953). When combined with Rudolph’s signature perspective drawings of both built and unbuilt projects, these publications conveyed a sense of informality and naturalness of lifestyle while exhibiting an inevitability and precision in their architectonic resolution.

At its height, the Sarasota School included Mark Hampton, Victor Lundy, Tim Siebert, Jack West, Gene Leedy, Carl Abbott, Bert Brosmith, Joseph Farrell, William Rupp, and Ralph and William Zimmerman, many of whom began their careers working for Rudolph and Twitchell. Each of these architects developed his own distinct qualities of space and form, from Lundy’s sweeping pagoda-like wood roofs (St. Paul’s Lutheran Church, Sarasota, 1958) to Leedy’s rhythmic lines of precast concrete beams (First National Bank, Cape Canaveral, 1963) to Abbott’s elegantly articulated geometries (Weld Residence, Boca Grande, 1966). The variety of designs within such a small community defied the stereotypical representation of modern architecture as lacking richness and diversity.

After starting construction on his four final Florida masterworks—Riverview High School in Sarasota (1958), Sarasota High School (1959), the Deering residence in Casey Key (1959), and the Milam residence in Ponte Vedra (1960)—Rudolph in 1958 was appointed dean of the School of Architecture at Yale University, where among his first students were Norman Foster and Richard Rogers. With the exit from Sarasota in the 1960s of Rudolph, Lundy, Hampton, Rupp, Farrell, Brosmith, and Leedy, the Sarasota School ended.

Although the American architectural profession has been slow to recognize the quality of the work of the Sarasota School (having failed to award Rudolph the American Institute of Architecture Gold Medal at his death in 1997), it received extensive and immediate international attention. Typical is the experience of British architects and Team 10 founders, Alison and Peter Smithson, who, in their search for alternatives to the universal formula of the International Style in the early 1950s, were inspired by the works being built in Sarasota. The Sarasota School exemplified the concept of a regionally inflected modern architecture, true to the universal intentions of spatial liberation yet capable of engaging local climate, landscape, and building culture and demonstrating the significant benefits of an evolutionary rather than revolutionary development of modern architecture.

ROBERT McCARTER

Sennott R.S. Encyclopedia of twentieth century architecture, Vol.3 (P-Z). Fitzroy Dearborn., 2005. |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| GALLERY |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1947, Finney residence, Siesta Key, USA, Paul Rudolph |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1950, Cocoon House, Siesta Key, USA, McKEOWN Heal |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1951, the Leavengood residence, St. Petersburg, USA, Paul Rudolph |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1952, the Sandeling Beach Club, Siesta Key, USA, Paul Rudolph |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1952, the Walker Guest House , Sanibel Island, USA, Paul Rudolph |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1953, The Umbrella House, Lido Shores, USA, Paul Rudolph |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1958, St. Paul’s Lutheran Church, Sarasota, USA, Victor A Lundy |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| ARCHITECTS |

|

| |

FOSTER, NORMAN

ROGERS, RICHARD

RUDOLPH, PAUL |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| BUILDINGS |

|

| |

1947, Finney residence, Siesta Key, USA, Paul Rudolph

1950, Cocoon House, Siesta Key, USA, McKEOWN Heal

1951, the Leavengood residence, St. Petersburg, USA, Paul Rudolph

1952, the Sandeling Beach Club, Siesta Key, USA, Rudolph

1952, the Walker Guest House , Sanibel Island, USA, Paul Rudolph

1953, The Umbrella House, Lido Shores, USA, Paul Rudolph

1958, St. Paul’s Lutheran Church, Sarasota, USA, Victor A Lundy

1963, First National Bank, Cape Canaveral, USA, Gene Leedy

1966, Weld Residence, Boca Grande, USA, Carl Abbot |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| MORE |

|

| |

INTERNAL LINKS

Foster, Norman (England); Rogers, Richard (England); Rudolph, Paul (United States); Smithson, Peter and Alison (England); Team 10 (Netherlands)

FURTHER READING

“Four Churches by Victor Lundy,” Architectural Record 126.no.6 (December 1959)

Eugenia Bell, Paul Rudolph: Inspiration & Process in Architecture

Domin, Christopher; and Joseph King, Paul Rudolph: The Florida Houses, New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2002

Hiss, Philip, “What Ever Happened to Sarasota?” Architectural Forum 126, no. 5 (June 1967)

Howey, John, The Sarasota School of Architecture: 1941–1966, Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 1995

“Progress Report: The Work of Mark Hampton,” Progressive Architecture 39, no. 6 (June 1958)

Rudolph, Paul, The Architecture of Paul Rudolph, New York: Praeger, and London: Thames and Hudson, 1970

Rudolph, Paul, Paul Rudolph, New York: Simon and Schuster, and London: Thames and Hudson, 1971

Rudolph, Paul, Paul Rudolph: Drawings, edited by Yukio Futagawa, Tokyo: A.D.A.Edita, 1972; as Paul Rudolph: Architectural Drawings, London: Lund Humphries, 1974

“Sarasota’s New Schools: A Feat of Economy and Imagination,” Architectural Record 125, no. 2 (February 1959)

“The Sarasota School of Architecture,” Florida Architect, Convention Issue (September– October 1976)

West, Jack, The Lives of an Architect, Sarasota, Florida: Fauvre, 1988 |

| |

|

|